Building a semantic search engine in OpenSearch

Semantic search helps search engines understand queries. Unlike traditional search, which takes into account only keywords, semantic search also considers their meaning in the search context. Thus, a semantic search engine based on a deep neural network (DNN) has the ability to answer natural language queries in a human-like manner. In this post, you will learn about semantic search and the ways you can implement it in OpenSearch. If you’re new to semantic search, continue reading to learn about its fundamental concepts. For information about building pretrained and custom semantic search solutions in OpenSearch, skip to the Semantic search solutions section.

Semantic search vs. keyword search

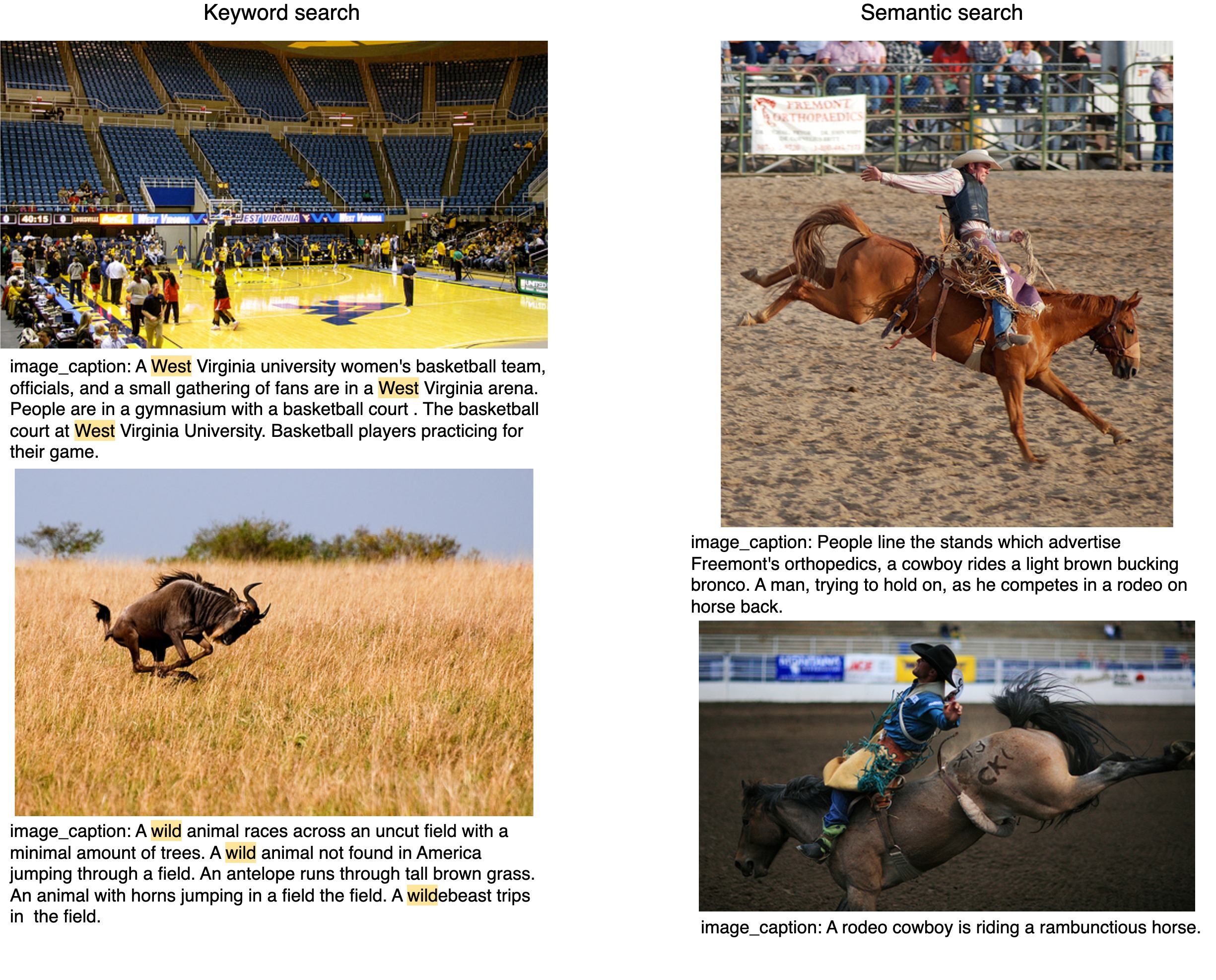

Imagine a dataset of public images with captions. What should the query Wild West on such a dataset return? A human would most likely expect it to return images of cowboys, broncos, and rodeos. While these results have no textual overlap with either wild or west, they are certainly relevant. However, a keyword-based retrieval system such as BM25 will not return images of cowboys precisely because there is no text overlap. Clearly, there are aspects of relevance that cannot be measured by keyword similarity. Humans understand relevance in a far broader sense, which involves semantics, contextual awareness, and general world knowledge. Using semantic search, we would like to build systems that can do the same.

To compare keyword search to semantic search, consider the following image, which shows search results for Wild West produced by BM25 (left) and a DNN (right).

Notice how on the left, keyword search surfaces West Virginia University and wild animal. On the right, neither caption contains the words wild or west, yet other terms in the caption form the basis for a closer match.

Search in embedding space

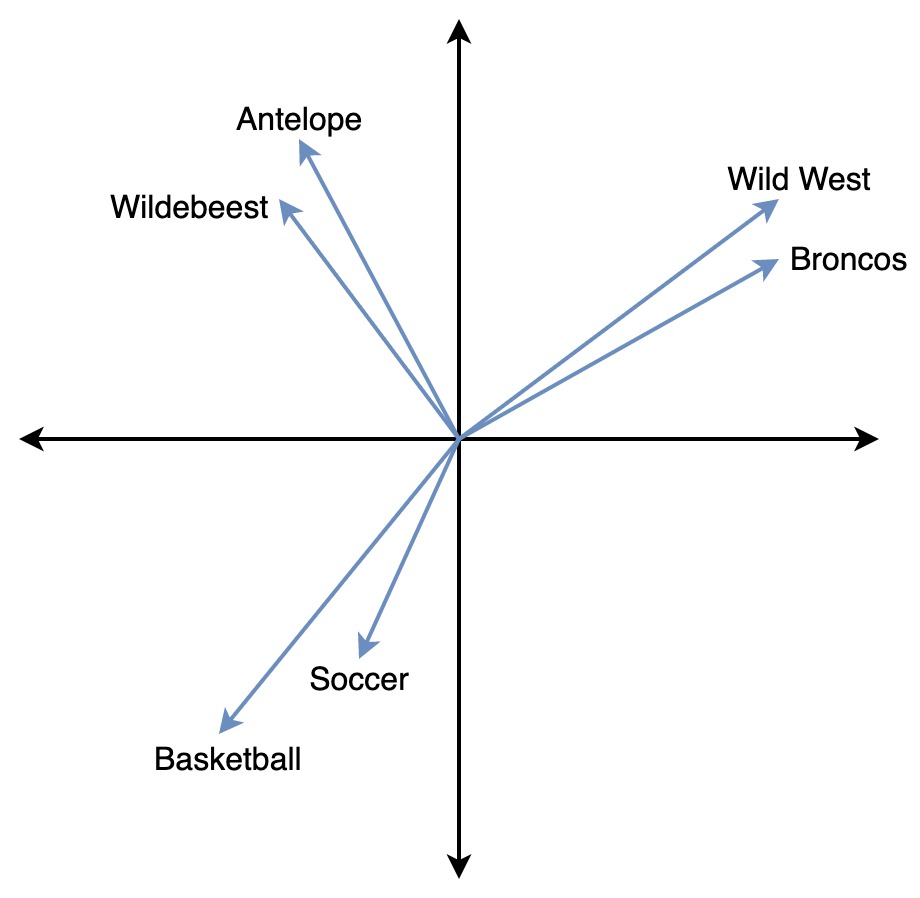

A DNN sees everything as a vector, whether images, videos, or sentences. Any operation that a DNN performs, such as image generation, image classification, or web search, can be represented as some operation on vectors. These vectors live in a very high-dimensional space (on the order of 1,000 dimensions), and the precise position and orientation of a vector defines a vector embedding. A neural network creates, or “learns”, vector embeddings so that it maps similar objects close to each other and dissimilar ones farther apart. In the following image, you can see that the words Wild West and Broncos correspond to closer vectors, both of which are far apart from the vector for Basketball, as expected.

In the context of web search, a neural network creates vector embeddings for every document in the database. At search time, the network creates a vector for the query and finds all the document vectors that are closest to the query vector by using an approximate nearest neighbor search, such as k-NN. Because the vectors of similar texts are mapped close to each other, a nearest neighbor search is equivalent to a search for similar documents.

The search quality crucially depends on the architecture and size of the neural network, because a large neural network learns more expressive embeddings. An example of such a large neural network is a transformer.

Transformers

A transformer is a state-of-the-art neural network that performs well on a variety of tasks. It is trained on lots of training data that includes millions of books, Wikipedia pages, and webpages. This training improves a transformer’s performance on tasks that require world knowledge and natural language understanding. For instance, the transformer learns that the term cowboy tends to appear near the term Wild West in many text documents; consequently, it maps the corresponding vectors close to each other. When such a transformer is further fine-tuned—trained on data that consists of (query, relevant passage) pairs—it learns to rank relevant passages higher in search results. Several such fine-tuned transformer architectures are publicly available, and you can use them off-the-shelf for web search.

However, a transformer that is trained on a particular kind of data has limited performance on data domains outside of the one it was trained on—this is a common issue with machine learning algorithms. One solution is to train a transformer on data from as many domains as possible. In principle, we can train a large enough network on vast amounts of data and expect it to “learn” everything. But the real problem is that more often than not, we do not have access to data from different domains. For instance, most organizations do not have public access to (query, relevant passage) pairs in the fields of medicine, finance, or e-commerce. We provide a solution to this problem using the technique of synthetic query generation.

In the rest of this post, you’ll learn how to build a semantic search solution in OpenSearch.

Semantic search solutions in OpenSearch

There are two types of models you can use to build a semantic search engine in OpenSearch:

- Pretrained: A ready-to-go model that you can download from a public repository

- Tuned: A custom model that uses synthetic query generation

Both options allow you to build a powerful search engine that is straightforward to implement. However, both come with tradeoffs: A pretrained model is easier to use, while a tuned model is more powerful.

Option 1: Semantic search with a pretrained model

A readily available pretrained model requires minimal setup and saves you time and effort of training. Follow these steps to build a pretrained solution in OpenSearch:

- Choose a model. We recommend the TAS-B model that is publicly available on HuggingFace. This model maps every document to a 768-dimensional vector. It has been trained on the MS Marco dataset and demonstrates impressive performance on datasets that belong to domains outside of MS Marco [BEIR 2021].

- Make sure the model is in a format suitable for high-performance environments. You can download the TAS-B model and some other popular models that are already in the correct format. If you are using another model, download the model and then follow the instructions in the Demo Notebook to trace Sentence Transformers model to convert it into a format suitable for high-performance environments, such as TorchScript or ONNX.

- Upload the model to an OpenSearch cluster. Use the model-serving framework to upload the model to an OpenSearch cluster, where it will create a vector index for the documents in the dataset.

- Search using this model. Create a k-NN search at query time with the OpenSearch Neural Search plugin. To learn how to create a k-NN search, follow the steps in the Similar document search with OpenSearch blog post.

For those interested in semantic search performance, we will be releasing detailed benchmarking documentation in an upcoming blog post. This documentation will include benchmarking data such as query latency, ingestion latency, and query throughput.

Option 2: Semantic search with a tuned model

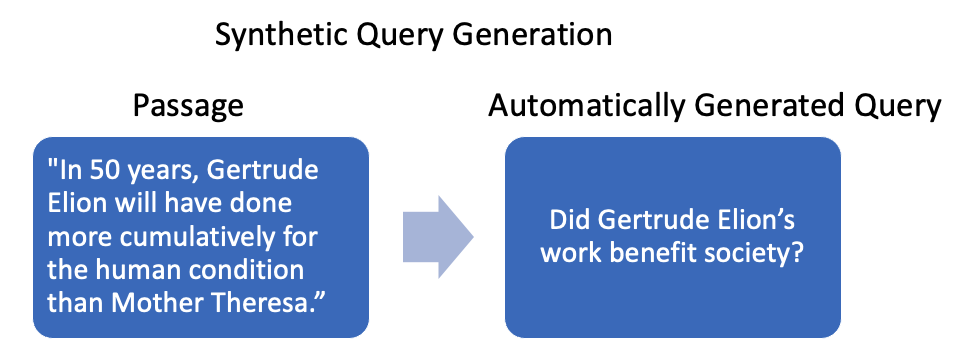

To build a custom solution, you ideally should have a dataset that consists of (query, relevant passage) pairs from the chosen domain in order to train a model so that it performs well on that domain. In the context of OpenSearch, it is common to have passages but not queries. The synthetic query generation technique circumvents this problem by automatically generating artificial queries. For example, given the passage on the left in the following image, the synthetic query generator automatically generates a question similar to the one shown on the right.

A medium-sized transformer model such as TAS-B can then be trained on several such (query, passage) pairs. Using this technique, we trained and released a large machine learning model that can create queries based on passages.

Performance

We conducted several tests to measure the performance of our technique. We generated synthetic queries for nine different challenge datasets and trained the TAS-B model on the dataset that contained the generated queries. When combined with BM25, our solution provides a 15% boost in search relevancy (measured in terms of nDCG@10) compared with the search relevancy provided by BM25 alone. We found that the number of synthetic queries generated per passage drastically affects search performance, with more queries leading to better performance. Additionally, we found that the size of the synthetic query generator model also affects downstream performance: Larger models lead to better synthetic queries, which in turn lead to better TAS-B models.

Try it

To try the synthetic query generator model, follow the end-to-end guide in the Demo Notebook for Sentence Transformer Model Training, Saving and Uploading to OpenSearch. After you run this notebook, it will create a custom TAS-B model tuned to your corpus. You can then upload the model to the OpenSearch cluster and use it at query time by following the steps in the Similar document search with OpenSearch blog post.

Next steps

If you have any comments or suggestions regarding semantic search, we welcome your feedback on the OpenSearch forum.

We’ll be releasing blog posts about benchmarking studies, an end-to-end guide to setting up a custom solution, and posts about new models and better neural search algorithms in the coming months.

References

- Attention is all you need, Vaswani et al. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.1706.03762

- Language Models are Unsupervised Multitask Learners, Radford et al. https://d4mucfpksywv.cloudfront.net/better-language-models/language-models.pdf

- Sentence-BERT: Sentence Embeddings using Siamese BERT-Networks, Reimers et al. https://www.sbert.net/index.html

- Efficiently Teaching an Effective Dense Retriever with Balanced Topic Aware Sampling, Hofstätter et al. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2104.06967

- Synthetic QA Corpora Generation with Roundtrip Consistency, Alberti et al. https://aclanthology.org/P19-1620/

- Embedding-based Zero-shot Retrieval through Query Generation, Liang et al. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2009.10270